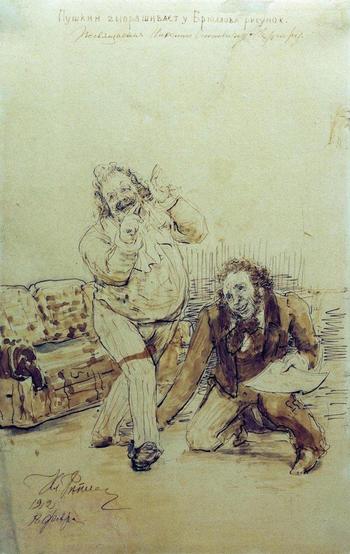

In 1914, the illustrated weekly Niva published a curious sketch by the veteran painter Il΄ia Repin, Pushkin vyprashivaet u Briullova risunok (Pushkin Begging Briullov for a Drawing), 1912 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Il΄ia Repin, “Pushkin Begging Briullov for a Drawing” (1912).

A noticeable departure from the more familiar, formal portraiture of the classic Russian figures Aleksandr Pushkin and Karl Briullov, this playful representation demonstrates the ease with which the artist treated these two venerable cultural icons, as well as their continued presence in the Russian public sphere and the audience's basic familiarity with them. Whereas Pushkin's status as national poet had been firmly secured by the major commemorations near the end of the nineteenth century, Briullov was a more recent addition to the pantheon of Russian greats. Not only did Repin place him on equal footing with Pushkin in this drawing, but one can also read a defiant suggestion of Briullov's superiority vis-à-vis the kneeling poet.

For all this irreverence, Repin's ironic sketch captures the changed status of the artist in popular imagination: although artists and their likenesses per se were not a novelty in Russian society, by the second half of the nineteenth century the celebrity painter ceased being an isolated phenomenon and became part of public culture. This article traces the evolution of the image of the famed Russian painter of Huguenot descent, Karl Briullov (1799–1852), starting from the Academy's talented student, to a larger-than-life Romantic genius, to the hero of major public celebrations, and finally to the target of caricature and anecdotes. Predictably, this metamorphosis correlates closely with changes in the social climate and artistic taste over the course of the long nineteenth century; it was also subject to rather arbitrary modulations in contemporary public discourse.

Although perhaps not the most original or best-known artist today, Briullov became the first Russian painter to achieve international renown during his lifetime and posthumous recognition as the founder of an entire Russian school of art (see Figure 2). How did Briullov earn his reputation as a “world-famous genius” (mirovoi genii)? One can argue that Briullov's fame rested on his exquisite paintings; his reputation skyrocketed around 1834, when his masterpiece, Poslednii den΄ Pompei (The Last Day of Pompeii), 1830–1833, arrived in Russia from Italy. Briullov, however, was more than a famous artist. He was also the subject of critical and popular writing, a protagonist of memoirs, a character in fiction, and a literary hero. Many Russian writers, artists, and critics wrote about Briullov and his art. Even when the representation was far from flattering—as in Nikolai Leskov's unfinished novel Chertovy kukly (Devil's Puppets), 1890, where the famous artist appears as essentially a puppet of the ruler—the colossal figure of Briullov, having been amplified in copious laudatory writing in previous decades, continued to loom large in Russian society.

Figure 2. Karl Briullov, Self-portrait (1848)

Aside from the artist's intrinsic talent, it is crucial to consider the context in which Briullov rose to fame compared to the relatively modest place that Russian artists had traditionally occupied in society. Contributing to the changing perception of art and the artist were public celebrations of living and dead masters, reproductions of paintings in specialized and popular editions, studies in art history, and numerous fictional and journalistic accounts of the Russian art world. Russian literature served as the obvious model in this evolution, and art critics have emphasized this connection time and again. The canonization of Pushkin, Nikolai Gogol΄, and other classics helped advance the institutionalization of founding figures in the field of the visual arts as well. The celebration of Briullov's centenary in 1899—the same year that Pushkin was fêted as national poet for the second time—established the Russian painter as a venerable classic in a nationwide celebration of pictorial art.

Yet this same Briullov, nicknamed “the Great Karl” (velikii Karl) during his lifetime, was also widely criticized for being anti-national, outdated, and fake. Between the two celebrations framing his magnificent career—one in 1836, shortly after The Last Day of Pompeii’s arrival to Russia, and the second, in 1899, when the Academy posthumously anointed him head of the Russian school of art—Briullov was dethroned on many occasions by critics and artists alike. If we trace the radical shifts in Briullov's reputation—from Academy's darling to Peredvizhniki’s nemesis to the undisputed but unexceptional classic of Soviet art history—we shall see that the Great Karl was largely a puppet in the hands of generations of critics and fellow artists. The protagonist of major official tributes and wide-ranging public debates in the nineteenth century, Karl Briullov nevertheless has proven to be an accidental hero. Briullov is the protagonist of the present essay not so much because of his “greatness,” which many contested during his lifetime and beyond, but because the evolution of his extraordinary reputation demonstrates the vagaries of canon formation at a time when painters were joining the pantheon of the founding fathers of Russian culture near the end of the nineteenth century.

Briullov's brilliant career has been scrupulously researched and the reception of his individual works has been well documented in scholarship.Footnote 1 This essay does not attempt to provide an objective evaluation of the artist and his place in the art-historical canon. Rather, by focusing on mutations of Briullov's critical fortunes over successive eras, I treat “the Great Karl” as a discursive construct: malleable, fickle, and incomplete. As culled from contemporary sources, broadly available at the time but subsequently obscured, including ephemeral newspaper writing and unreliable fiction, the Karl Briullov that emerges in these pages is less a national colossus than a brittle bricolage of contested opinions.

Briullov's status as a cultural icon grew not just out of the highest professional accolades but, more significantly, the wide-ranging controversy that followed the artist throughout the decades and made him a living presence in society. Now fêted lavishly as national genius, now dismissed categorically as a fraud, Briullov became part of the popular imagination as a problematic character of sundry written texts, a literary figment more than a historical person. The discursive aspect of this cultural scenario was crucial in articulating the role of the painter in Russian society, as ongoing debates became the moving force in fashioning the image of the artist as national hero.

Underlying these debates are questions regarding the very status of canonical figures and founding fathers. The reception of Karl Briullov in imperial society and beyond highlights the haphazard process of inclusion and exclusion in canon formation and draws attention away from the historical artist and toward the contemporary public and its shifting tastes and opinions. The many versions of Briullov that coexist in the history of Russian art testify to the changing tastes of society and the very mutability of the canon. At pivotal moments of canonization, Briullov was caught between amateur and professional critics, between the incipient institutionalization and modernization of art discourse, and between neo-classicism, Romanticism, and Realism. This contestation between various groups at the turn of the twentieth century was taking place before any reliable textbooks or histories of Russian art were available. Following the obviously experimental nature of this early effort to devise the foundational narrative of Russian art, the afterlife of the artist's heritage was subject to the many shifts in interpretive trends in subsequent periods.

In reconstructing a historical scenario of how the image of an artist as a national hero was generated, disseminated, reproduced, and revised over successive eras, we discover the relativity of the selection process. Snapshots of the years 1836, 1899, 1914 and beyond give us a historical picture of what mattered to contemporaries at the time, and what social and political issues influenced the contingencies of value. This first experiment in art-historical canon formation was laden with controversy and ultimately proved untenable. It was, however, a productive endeavor in that it animated professional art discourse, ignited the public's interest in art, and stimulated dialogue between art and society. There was also something striking about Briullov's canonization: it was propelled by the written word more than pictorial imagery and it was assisted greatly not by textbooks or art experts, but the great Russian poet, Pushkin.

1836: The Arrival of the Hero

The exhibition of Karl Briullov's famous painting, The Last Day of Pompeii, was a remarkable event in the history of Russian art and an exceptional episode in the life of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts (see Figure 3). Briullov was one of the Academy's most brilliant students; he was also among the first beneficiaries of the recently established Society for the Encouragement of Artists, the support of which allowed him to advance his education abroad. He left Russia in 1822 and remained in Rome for the next thirteen years; many of his celebrated paintings, including The Last Day of Pompeii, were created in Italy.

Figure 3. Karl Briullov, The Last Day of Pompeii (1830–1833).

Prior to its arrival in Russia, Briullov's masterpiece generated “boundless enthusiasm” in Italy: cities organized receptions for the artist, poems were dedicated to him, and on the streets, he was greeted with “music, flowers, and torchlight processions.”Footnote 2 The painting resonated so loudly in Italy in part due to the topicality of the subject matter, with the excavations of Pompeii having recently resumed, along with the conspicuous success of an opera by Giovanni Pacini, L'ultimo giorno di Pompei (1825), which influenced Briullov directly. In turn, his masterpiece inspired the once popular novel by the Baron Edward Bulwer-Lytton, The Last Days of Pompeii (1834). Sir Walter Scott, who reportedly spent an hour in front of Briullov's canvas, called The Last Days of Pompeii an “epic.”Footnote 3 The painting was next exhibited at the Louvre, where the French Academy awarded it a gold medal, although the French press was noticeably unimpressed with Bruillov's famous canvas.

In August 1834, The Last Days of Pompeii arrived at the Hermitage on the wings of its European fame. Count Anatolii Demidov, who commissioned the painting, gifted it to Nicholas I; the latter accepted it graciously and summoned Briullov from Italy to assume a professorship at the Academy. Soon thereafter, The Last Day of Pompeii was put on public display. Many wrote about this special occasion, including Pushkin, Mikhail Lermontov, Evgenii Baratynskii, Vasilii Zhukovskii, and Aleksandr Herzen.Footnote 4 Gogol΄, for one, proclaimed it to be the “bright resurrection of painting” in an essay devoted to the artist, which was published as part of his Arabesques in 1835.Footnote 5 The written word was fundamental to securing Briullov's fame during his lifetime, in part due to the limited means for the dissemination of art in Russia before photomechanical reproduction of images became widespread near the century's end. Thus, prior to the arrival of The Last Day of Pompeii in St. Petersburg, several reproductions circulated in society that were not true copies but rather variations based on verbal descriptions of the masterpiece. Even when the painting was displayed in St. Petersburg, it remained a sort of “fairy tale” in Moscow.Footnote 6

On June 15, 1836, the Academy organized a gala reception, the first of its kind, to celebrate the “supereminent talent of one of the Academy's pupils.”Footnote 7 The reception itself was unprecedented. As Alexandre Benois, the cofounder and leading art critic of Mir iskusstva (World of Art), observed: “at that stuffy, bureaucratic time (chopornoe, kazennoe vremia), that dinner, with two orchestras, with Briullov's painting in the hall, with the laurel wreath, speeches, drunkenness, and tears of tenderness, appeared as something fantastic, some unearthly paradise …” Aspiring artists were overcome by the desire to be a Briullov.Footnote 8

Briullov mattered so much in Russia because of his international reception. Among the anecdotes that circulated in society was one about an Italian officer who recognized the artist's name when checking his travel documents and respectfully permitted his passage, despite the lack of proper identification papers. On another occasion, theatergoers in Milan joyfully offered their opera tickets to the famous author of Pompeii when he failed to secure himself a ticket at the box office.Footnote 9 Repin vividly recollects the mythology that surrounded the Great Karl: “How many fairy tales circulated among us artists about the great painters! The center of all miracles in art was ‘Brulov’ (this is what Briullov was called). It was said that he painted so ‘rapturously’ that his art was as three-dimensional (vypuklyi) as sculpture. And all the anecdotes and legends created from times immemorial about artists were connected with ‘Brulov.’”Footnote 10 The wide recognition of Briullov after his arrival to Russia is also supported by a number of popular images of the artist that rendered the public's “idol” as a familiar and accessible character. At the height of Briullov's popularity, small-scale sculptural representations of the artist apparently could be found in many homes.Footnote 11 Nikolai Stepanov, the future co-founder of the satirical journal Iskra (Spark), created some eighty statuettes-caricatures of literary and artistic figures in the late 1840s–early 1850s, including Briullov. Briullov was also included in Stepanov's series of about forty miniature busts of contemporary celebrities. These “souvenirs” were readily available for sale in the Beggrow shop on Nevsky Prospect and enjoyed consistent popularity.Footnote 12 It was this legendary Briullov who dared refuse to paint the portrait of Emperor Nicholas I himself when the latter was tardy for his first session.Footnote 13

Briullov defied the image of a typical artist trained by the Academy, the institution that regulated much of artistic production in imperial Russia. As Elizabeth Valkenier summarizes, the Academy in the earlier half of the nineteenth century served as “an instrument that molded artists into servitors of the state, subordinated art to the needs and tastes of the Court, and controlled artistic life throughout the country.”Footnote 14 The channels of communication between art and society at the time were largely limited to triennial exhibitions and occasional reviews. This is not to deny the existence of individual talent; major Russian artists of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, such as Dmitrii Levitskii, Anton Losenko, Vladimir Borovikovskii, and Orest Kiprenskii, had all enjoyed critical recognition and success. Their art, however, lacked visibility in society at large—something that regular exhibitions, public celebrations, and attendant critical commentary would afford in the following decades. More than anything, as Dmitrii Sarabianov comments, Briullov marked a “colossal leap for Russian consciousness, a leap from the previous state of artistic subjugation into creative freedom.”Footnote 15

More substantial efforts to commemorate the Great Karl took place in Russia after his death in 1852. The artist's reputation was officially solidified when he was selected as the only painter to be included in the pantheon of Russian cultural figures represented in the Millennium Monument (see Figure 4). Designed by the young artist Mikhail Mikeshin, who won a national competition for his proposal, the Millennium Monument was unveiled in Novgorod in 1862. It aimed to represent Russian history and culture in its entirety and included, aside from the prescribed historical compositions occupying the upper tiers of the monument, 109 figures of distinguished rulers, military leaders, clerics, officials, and representatives of science and the arts. Sixteen creative artists figured among them, including a single painter, Karl Briullov. In sharing space on the monument's bas-relief with Pushkin, Gogol΄, Mikhail Glinka, and a handful of others, the artist was symbolically admitted into the emerging canon of Russian artistic culture. It would seem that by 1862, Briullov had won unanimous endorsement as the great Russian artist, in official and public circles alike. The public's support is worth underscoring in particular: although the monument originated with the Committee of Ministers and was personally supervised by the emperor, the process of selection of relevant figures, which began in Mikeshin's studio with the participation of historian Nikolai Kostomarov, poet Taras Shevchenko and novelist Ivan Turgenev, and which was partially aired in the press, allowed for a degree of public participation.Footnote 16

Figure 4. The Millennium Monument, fragment (1862)

Aside from being memorialized in bronze, Briullov emerged shortly after his death as a heroic figure in several published memoirs, as well as in Shevchenko's work of fiction Khudozhnik (The Artist), 1856. In the pages of much of this commemorative literature, Karl Briullov as historical person seems to have transcended his earthly status, reaching to the heights of mythology. Among many other tributes, the sculptor and art historian Nikolai Ramazanov made public his “Reminiscences of Briullov.”Footnote 17 In 1855, three years after the Great Karl's death, his student, the Russian-Ukrainian artist Apollon Mokritskii, published his reminiscences in the pages of Otechestvennye zapiski (Notes of the Fatherland).Footnote 18 Another of Briullov's students and later his biographer, Mikhail Zheleznov, who published Briullov's letters as well as a number of articles, wrote the following year about Briullov's importance in art in Sovremennik (Contemporary).Footnote 19

The title character of Shevchenko's partly autobiographical novella The Artist is a talented serf artist whose fortunes change miraculously when, under the patronage of the writer Vasilii Zhukovskii and the Great Karl himself, a group of St. Petersburg intelligentsia undertakes to buy the young man his freedom. To raise the necessary sum of 2,500 rubles, Zhukovskii asks Briullov to paint his portrait, which is then sold in a lottery. Freed in such a way in 1838, Shevchenko's fictional artist (just like Shevchenko himself) is able to enroll in the Academy with Briullov as his mentor.Footnote 20

In the pages of Shevchenko's novella, the historical painter Briullov is represented as indeed a hero, an affirmative role that was novel both for historical and fictional artists alike. Although written soon after Briullov's death, Shevchenko's novella was published in Kievskaia starina only in 1887, before which this fictional portrait of a successful and socially aware Russian artist remained out of the public view. The literary representations of artists that were available in the first half of the nineteenth century—and fictional narratives comprise a large portion of art-related public discourse at the time—were for the most part versions of the Romantic conception of the artist as an outsider, a failure, a tragic character. Gogol΄’s Chartkov, the protagonist of the short story “The Portrait” (1835; 1842), is such a character, as is the hapless Piskarev of “Nevsky Prospect” (1834), who mistakes a prostitute for a muse one ill-fated evening, and perishes after failing to reconcile his beautiful dream with banal reality. Vladimir Odoevskii's tale “Zhivopisets” (“The Painter”), 1839, depicts another artist, one who refuses to paint commissioned portraits and store signs, pursuing instead an elevated subject unbeknownst to all and ultimately descending into madness.Footnote 21 This fictional model of an artist disengaged from reality survived the modernizing Great Reforms and beyond, as it did in Ivan Goncharov's Obryv (The Precipice), 1869, which was initially titled “The Artist.” For the most part, the artist remained an elusive figure in the first half of the nineteenth century; Vissarion Belinskii proposed a delicate analogy to describe the type: “Our artist remains a riddle, as ephemeral as a woman.”Footnote 22 Compared to these evasive fictional portraits of the artist, Karl Briullov's remarkable reputation must have struck contemporaries most forcibly.

1860s: The Fallen Idol

The first consistent efforts to undo the cult of the Great Karl date to the radical 1860s. The turn toward nationality, which, as the indefatigable critic Vladimir Stasov announced in 1869, defined a “new epoch” in the history of the fine arts in Russia, changed every aspect of artistic production.Footnote 23 New channels of communication between art and society opened in the context of the Great Reforms (1860–1874): the era saw the proliferation of museums and exhibitions, the intensification of public debates, and the advancement of art criticism. Many journalists observed that the Russian public, which had until recently been indifferent to art, was now showing growing engagement with the kind of art that “reflected its life and its truth.” This pronounced interest in art was in itself a noteworthy phenomenon, and reviewers of exhibitions wrote about the crowds of visitors almost as much as they did about the paintings.Footnote 24 It was at this time that discourse on the arts left the halls of the Academy and became the property of the public sphere. Russian painters soon became household names. A group of independent artists known as “The Association of Traveling Art Exhibitions,” or Peredvizhniki (the Itinerants), helped popularize Russian art tremendously. In the course of their first few exhibitions, which brought art to the Russian provinces, the Peredvizhniki effectively became what Valkenier describes as “an alternate artistic center” to the Academy.Footnote 25

In contrast to the first half of the nineteenth century, when all artists were like “one big factory of clichés, producing Italian women at fountains and pseudo-historical subjects,” as Stasov wrote in an obvious jibe at Briullov's famous Italian scenes, the new generation turned to themes as diverse (and often as unattractive) as ordinary Russian life itself.Footnote 26 Reform-era artists and critics actively criticized the obsolete aesthetics of the St. Petersburg Academy and the “murderous scrupulousness” of classical themes—“the same Ajaxes, Achilleses, Herculeses, and Andromedas” that every European academy had “chewed over and over again.”Footnote 27 Next to such neoclassical canvases as Fedor Bruni's Death of Camilla, Sister of the Horatii (1824), or Briullov's The Last Day of Pompeii, Vasily Perov's drunken Orthodox clergy or Ivan Kramskoi's peasants in tatters looked frighteningly familiar indeed. Repin's enormously popular Burlaki na Volge (Barge Haulers on the Volga), 1870–1873, depicting weary men in rags engaged in inhumane labor, exemplifies this spirit of national realism that defined reform-era art production; it was received by contemporary society with no less enthusiasm than was Briullov's masterpiece several decades earlier.

Along with personages like these nameless peasants that were previously considered inappropriate for depiction, the artist himself became the subject of representation—a modern hero competing with Greek and Roman models. Earlier in the century, Briullov had contributed fruitfully to this evolving tendency as well. Among Bruillov's plentiful depictions of his contemporaries, the artist's several self-portraits represent excellent examples of Romantic portraiture. This changing perception of artists was later institutionalized by the Tret΄iakov Gallery, when the Moscow merchant Pavel Tret΄iakov conceived of a special portrait gallery within his collection devoted to the makers of Russian culture—well-known writers, composers, painters, and architects—and commissioned numerous portraits for it. Famous portraits by Briullov, including those of Zhukovskii, the architects Ippolit Monighetti and Aleksei Gornostaev, and the writer Nestor Kukol΄nik, which Tret΄iakov acquired for the occasion, were the obvious choices to provide a foundation for the new Russian pantheon. Although Tret΄iakov's project remained unfinished, his portrait gallery has since come to represent the iconography of modern Russian culture.Footnote 28 Some of these portraits were commissioned by Tret΄iakov specifically for his gallery; others were introduced during the Peredvizhniki shows. Portraits of Russian writers obviously outnumbered other categories, but Tret΄iakov's pantheon also included pictorial representations of Russian musicians, composers, and actors, including Anton Rubinshtein, Nikolai Rimskii-Korsakov, Aleksandr Serov, and Mikhail Shchepkin.Footnote 29 Portraits of artists were no less plentiful. Repin and Kramskoi were especially prolific portraitists, creating many images of their fellow artists. These likenesses became a part of public culture via museum and exhibition displays, as well as ample commentary in the press. The artist was turned into a celebrity when his portrait was put on display in the Tret΄iakov Gallery.

The metamorphosis of literary representations of the artist went hand in hand with new collecting and exhibiting practices. Emblematic of this change is Vsevolod Garshin's short story “Khudozhniki” (The Artists), 1879, where two coexisting traditions, the old Academic training and the new realist aesthetics, collide dramatically. Unlike his fellow artist bearing the rather suggestive name of Dedov, who stands for academism, the realist artist Riabinin eschews an Academy-sponsored trip abroad in order to use his talent in service to society. Riabinin personifies the new idea of the artist as a reformer, someone whose role is, in the words of one critic, to “serve life and become one of the prime movers in the development of social consciousness.”Footnote 30

In the context of the more democratic trends in art advanced by the Peredvizhniki in the second half of the nineteenth century, the image of the Russian colossus Karl Briullov, now deceased, was undergoing a thorough revision. The prolific and influential Stasov helped frame critical discourse aimed at the Academy and the neoclassical tendencies that it represented. Against the background of euphoric responses to the author of the great Pompeii that had largely defined the reputation of the artist in the first half of the nineteenth century, Stasov's was among the first voices of dissent. Stasov himself admired Briullov only a decade earlier, as is obvious from his 1852 elegiac article in Otechestvennye zapiski.Footnote 31 In 1861, however, the same Briullov who had loomed large over the art world for so long became an easy target for criticism. In his self-appointed role as the main proponent of national realism in art, Stasov bluntly denied the celebrated artist any national originality—Stasov's yardstick for greatness—writing that “Briullov's works contain nothing Russian, nothing national, no new elements which could not be found in the works of other nations.”Footnote 32 Separated by a decade, these two perceptions—one celebratory, the other—dismissive, reflect the shifting perspective in art appreciation that was taking place in Russian society at mid-century.

The issue of Briullov's significance became urgent in the course of the aesthetic debates of the 1860s. Of course, Stasov and the liberal critics who followed in his steps represented but one view on the Academy and its veterans. Even if anti-establishment figures were more outspoken, the reform-era art world was far from monolithic, embracing conservative, liberal, and radical ideological positions. Nor was the Academy as ominous an institution as the generation of the 1860s represented it.Footnote 33 While some turned against the Academy, other critics and patrons continued to support it with undiminished enthusiasm, something that Garshin's story represents very perceptively. The coexistence of the Academy's shows and the Peredvizhniki exhibitions, as well as journals and newspapers of varying tastes and ideological positions that sustained these aesthetic debates for several decades, testifies to the diversity of the Russian art scene and its plurality of expression.

Whether their voices were raised in praise or condemnation of Briullov, critics invariably turned to the Great Karl as a point of departure in modern Russian art history; for them he was a sort of role model, either positive or negative depending on one's orientation. Freighted with symbolic value, Briullov's name easily slipped into fictional realms as well. It was in the pages of Turgenev's novel Dym (Smoke), 1866, for instance, that Briullov received the memorable moniker “bloated mediocrity” (pukhlaia nichtozhnost΄), a sentiment shared by many in the 1860s and 1870s.Footnote 34 Turgenev's character, the well-educated Westernizer Potugin, who doubts the existence of an authentic Russian culture, including Russian art, makes the following pronouncement: “Russian art! … I know all about Russian limitations, and I know Russian impotency also, but as for Russian art, excuse me, but I have never met with it. For twenty years in succession we bowed down before that bloated cipher, Briulloff, and imagined, if you please, that a school had been founded among us, and that it was even destined to be better than all the others … Russian art, ha-ha-ha! ho-ho!”Footnote 35 A fleeting reference made to advance a larger argument, Briullov metonymically comes to stand for the entire Russian school of art whose existence was much debated in the periodical press. Even though Turgenev admitted to the shortcomings of his Smoke, which was overall not well received, the writer's apt “bloated mediocrity” stuck to Briullov as firmly as “world-famous genius” had in earlier decades. One artist that Briullov's critics, including Turgenev and later Benois, liked to extoll as a counterpart to Briullov was his contemporary, Aleksandr Ivanov.Footnote 36 A deeply religious artist, Ivanov worked on his masterpiece, Iavlenie Khrista narodu (The Appearance of Christ before the People), 1837–1857, for twenty years, also in Rome. Although this major paining did not achieve the success of Briullov's Pompeii, Ivanov, who died shortly after his canvas was displayed in Russia in 1858, was recognized as an important, albeit controversial, figure: the Slavophile philosopher Aleksei Khomiakov acclaimed him as a “sacred artist” (sviatoi khudozhnik), just as Stasov praised Ivanov as a “deep and genuine realist.”Footnote 37

The theme of conflict between different aesthetic principles, which was topical in the 1860s, returns in Leskov's unfinished novel The Devil's Puppets, the first installment of which was published in the politically moderate journal Russkaia mysl΄ (Russian Thought) in 1890. Leskov's protagonist, a talented artist named Febufis, the son of Phoebus (Apollo), is only a vaguely disguised Karl Briullov. The historical Briullov had also been compared to that deity; Mokritskii, for instance, wrote in his memoirs, “I imagined him no other than in the guise of the Apollo Belvedere.”Footnote 38 The action takes place in the first half of the nineteenth century in Rome, where Febufis first studies and then practices art with great success. At the height of his fame and notoriety, Febufis departs from Rome with a young Duke from an unnamed land who is rumored to possess extraordinary riches and expert knowledge of fine arts—someone whom critics were quick to recognize as Nicholas I. As a beneficiary of official patronage, Febufis is soon rewarded for his service to the court with a lucrative position overseeing art production throughout the Duke's land. The published installment ends with Febufis's marital troubles and his increasing discontent with his chosen path. Drafts of the remaining parts of the novel, which were never published, indicate that Febufis escapes his inglorious predicament through suicide.Footnote 39 Here Briullov is, if anything, a mock-hero, one who passively accepts royal patronage, practices the ideology of disinterested art, and fulfills no useful service to society. Leskov's artist fails society and his vocation; although separated from Smoke by almost three decades, this fictional representation of Briullov reads to a great degree as an elaboration on Turgenev's “bloated mediocrity.”

In this mirror of imaginative literature, we find the reflection of the artist's changing role in society. But literature also magnifies and generalizes: from a historical painter, Karl Briullov turns into a conformist type—one that in the context of the late nineteenth century was increasingly under attack, first by the Peredvizhniki, then by the Mir iskusstva group and the avant-garde. This growing chorus of criticism, however, while topical and sharp, did not destroy Briullov's reputation, but instead only served to amplify it: no other artist was fêted as much as Briullov in imperial Russia.

The Crux of Canonization

The critical concept of the canon and its application to literary studies has been a subject of vehement debates in academic circles for decades.Footnote 40 The formation of the art-historical canon is a more recent topic, and the Russian version of it is still being written.Footnote 41 Without dwelling on a plethora of scholarly conceptualizations, or defending the concept whose very usefulness has been recently called into question, the present discussion takes as a given the non-essentialist view of canonicity, which embraces rediscoveries and revisionism as a necessary part of the process of canon formation. In the context of Russian cultural politics, the canon matters first of all as an expression of national heritage; its existence implies the longevity and continuity of a culture. That said, precisely what comprises a particular culture is always open to negotiation, thus the constantly shifting contours of the canon's content. Canon formation entails both short-term and long-term processes; it is neither entirely contingent nor permanent. If the long-term process can be viewed as a stabilizing, accumulative mechanism that regulates culture, the momentary fluctuations in taste and opinion generated by different institutions and groups productively disrupt (though not necessarily undermine) the permanent architecture of the canon. Briullov's art became a battleground for canon formation at the turn of the century as it got embroiled in this conflict between the necessary concept (the need for an articulate tradition in the visual arts) and the changeable content (the fluctuating definitions of that tradition in the making).

To a certain extent, the shifting fortunes of major Russian artists follow the “rules” guiding the process of inclusion and exclusion. The alternating waves of appreciation and criticism that shaped Briullov's reputation, while impressive in their amplitude, do not deviate from the paradigm established by Frank Kermode, who argues for the provisionality of canons: “Changes in the canon obviously reflect changes in ourselves and our culture. It is a register of how our historical self-understandings are formed and modified.”Footnote 42 In relation to art history, Hubert Locher even proposes to talk about canons in the plural: “We have thus not one ‘art-historical canon’ but competing canons, canons embodying national identity, or canons for groups of individuals within it, who are trying to develop a specific identity, not in contradiction, but in relation to society at large by using the reference system of art.”Footnote 43 Major shifts in the appreciation of national heritage tend to correlate with significant changes in society, which is obvious in Russia as elsewhere.

But these modulations are also open to chance. As Kermode observes: “Reception history informs us that even Dante, Botticelli, and Caravaggio, even Bach and Monteverdi, endured long periods of oblivion until the conversation changed and they were revived.”Footnote 44 An element of chance certainly played a major role in the critical reception of Briullov. Significantly, Grigorii Sternin, an acute and perceptive critic of artistic life in imperial society, refers to the artist's “divine” reputation as “the incident of Briullov” (sluchai Briullova).Footnote 45 Indeed, Briullov's case in Russian art history highlights the centrality of interpretation and evaluation in canonization practices, for neither artists nor artworks become canonical by themselves. This work is usually carried out by mediating institutions (academies, publishing houses, departments of art history) and important mediators (critics, curators, patrons).Footnote 46 That Russia so obviously lacked an established system of art appreciation for much of the nineteenth century only added to the accidental nature of first attempts at canonization in the field of art history.

Jubilee celebrations, exhibitions, monuments, publications, museums—all these various opportunities for commemoration of the classics contributed to the early efforts to articulate a canon of Russian culture in imperial society.Footnote 47 Through public celebrations during the last decades of the nineteenth century, many of the key producers of culture were turned into luminaries. A veritable “jubilee mania” swept through Russian society near the end of the imperial period, as the public engaged in celebrations of all kinds, ranging from those glorifying the military and state, to religious holidays and festive commemorations of cultural figures.Footnote 48 Dostoevskii's famous paean to Pushkin in 1880 was among the earliest utterances in this public dialogue on the celebration and canonization of Russian classics. Two decades later, Pushkin became a national institution when a massive centennial of the poet's birthday was commemorated in 1899 at the tsar's behest.Footnote 49 Russian society similarly honored the jubilees of Gogol΄ and Chekhov, as well as the eightieth birthday of the “living classic” Lev Tolstoi, among many others. The appearance of several museums dedicated to Russian authors permanently secured their place in public culture. Following the first such institution, the Pushkin museum at the Lyceum that opened in 1879, museums memorializing Lermontov, Tolstoi, and Chekhov were soon established.Footnote 50 Next to these literary talents, the founding figures of Russian music and painting were celebrated as well.

Yet the perception of Russian visual arts in society was largely defined by derivation and delay: Russian art was secondary to both European art and Russian literature. We should recall that a systematic study of art was not available in Russia prior to the mid-nineteenth century, when a formal art history department was organized at the Moscow University in 1857.Footnote 51 Curiously, one of the initiators of the new discipline was philologist Fedor Buslaev. When decades later count Valentin Zubov's Institute of Art History opened in St. Petersburg, it was still lauded in the press as a novel undertaking.Footnote 52

Nor did Russia have any serious studies or textbooks on native art before the century's end. Among the significant contributions that appeared around the turn of the century were Nikolai Sobko's unfinished Slovar΄ russkikh khudozhnikov s drevneishikh vremen do nashikh dnei (Dictionary of Russian Artists from Ancient Times to Our Days), the first three volumes of which came out in 1894–1900, Istoriia iskusstv by Petr Gnedich (The History of Art), 1897, Benois’ Istoriia zhivopisi v XIX veke. Russkaia zhivopis΄ (History of Painting in the Nineteenth Century: Russian Painting), 1901–2, and Aleksei Novitskii's Istoriia russkogo iskusstva s drevneishikh vremen (History of Russian Art Beginning from Ancient Times), 1903. The first extensive scholarly edition, a multi-volume history of Russian art compiled by Igor΄ Grabar΄, with contributions by leading art historians, came out in installments in 1909–1914 and remained unfinished; it was greeted as a major milestone in the discipline's history.Footnote 53

The institutional aspect is important because, while critical commentary authored largely by amateurs was plentiful, it muddled the interpretation of visual arts as much as it popularized them. Benois’ assessment of the contemporary art scene captures the predicament of the emergent discipline at the turn of the century:

Just how little art has entered our life can best be shown by the views held by our smartest and most educated people on the topic. Starting with Pushkin, who prostrated himself (valialsia v nogakh) in front of Briullov's “genius,” and ending with Leo Tolstoi, whose sorry treatise on art was based on a fundamental misunderstanding—all of them without exception, even Gogol΄ and Dostoevskii, had the most hazy and incoherent ideas about painting, sculpture, and architecture.Footnote 54

This institutional vacuum at the turn of the century affected the reception of art on a popular level. Alongside the proliferation of Russian classic texts in print at the turn of the century—a trend analyzed brilliantly by Jeffrey Brooks—visual images were being rapidly disseminated in a variety of printed editions (including inexpensive illustrated supplements), exhibitions, and catalogues. But unlike literary figures, whose names by that time “had entered into the rhetoric of a new language of national pride and self-awareness,” Russian artists were admitted into the national canon with a delay, as evidenced by widely circulated annual calendars.Footnote 55 According to Brooks's estimate, 20% of the entries on noteworthy events and significant people were devoted to Russian writers. By contrast, only three artists appear in the list of Suvorin's popular Russian Calendar for 1911: Vasilii Vereshchagin, Ivan Aivazovskii, and Karl Briullov.Footnote 56

Against this backdrop of interpretive chaos, the jubilee celebration of Karl Briullov was a major milestone in the canon-building project. It was also rife with controversy. The appointment of founding geniuses in various national traditions—Homer, Dante, Goethe, Shakespeare, Pushkin—is central to the articulation of an idealized cultural heritage that the canon represents.Footnote 57 On the one hand, Karl Briullov, a bright and charismatic personality, a romantic genius of international renown, was a natural choice for the vacant position of national hero in the visual arts. On the other, his very nomination as the founding father was questioned in the course of fierce debates occasioned by the jubilee. During this first attempt to articulate and negotiate the position of the founding genius in the visual arts, Briullov's proximity to Pushkin was not the least important factor.

1899: Briullov's Centennial

In 1899, major celebrations of both Briullov and Pushkin took place, inviting obvious analogies that were continually played up in the press. But whereas the first Pushkin jubilee in 1880 served to reconcile opponents and unite the Russian intelligentsia (Pushkin served as a “conciliator,” in Marcus Levitt's words), Briullov's first jubilee was all about discord.Footnote 58 Far from being a harmonious holiday, the painter's canonization served to underscore differences among individual artists and groups and even challenged the hero of the occasion himself.

Briullov's centennial was celebrated on December 12, 1899 in both capital cities and received extensive coverage in the periodical press. Both voluntary associations and the official Academy, as well as its nominal adversaries, the Peredvizhniki, contributed to the festivities. While jubilee celebrations of cultural figures were not unusual at that time, Briullov's commemoration was the first such public event that celebrated a painter as a maker of culture. For this special occasion, exhibitions were organized in Moscow and St. Petersburg; special meetings were called; commemorative books, brochures, and reminiscences were published; and a great number of articles and reviews appeared as well.Footnote 59 In Moscow, a festive gathering was organized by the Moscow Society of the Lovers of the Arts (Obshchestvo liubitelei khudozhestv). St. Petersburg's celebratory meeting was hosted by the Academy of Fine Arts. The occasion was so thoroughly covered in the press that the Mir iskusstva journal made the following sweeping generalization: “All the journals and newspapers considered it their duty to report on the festivities in honor of Briullov that took place on December 12th at the Academy of Fine Arts. Everybody already knows that a great number of people attended, that everything proceeded very decorously and even impressively.”Footnote 60

But it was a laudatory and apparently impromptu speech by Repin that launched a wide-ranging public debate. Contemporaries’ responses to Repin's tribute, excerpts of which quickly appeared in the newspapers, were initially euphoric, until Mir iskusstva joined in the conversation by calling Repin's celebratory speech a gaffe (nedorazumenie) lacking the most important thing—an idea (mysl’). This altercation was expressive of animosity between young nonconformists, attuned to new artistic developments in the west, and the former rebel turned institution, with whom Mir iskusstva collaborated briefly. In the 1890s, Repin assumed a post at the reorganized Academy, in the reforms of which he believed sincerely, and himself became part of the tradition which he demonstratively challenged several decades earlier.Footnote 61

As a caustic controversy unfolded at the turn of the century, Repin's speech not only became an event in its own right, but helped advance Briullov's celebration, which initially centered in artistic circles, into the larger public view. Responding to Mir iskusstva’s provocation, Repin published a riposte in the liberal newspaper Rossiia (Russia); this text was reproduced in Mir iskusstva, followed by the journal's own response. There was not much about Briullov per se in this exchange; instead, Repin accused Mir iskusstva of presumptuously acting as а “corporal of our society's artistic taste” and disregarding “recognized authorities.” Defending its position, Mir iskusstva challenged the veteran artist to name any scholarly publications on the history of Russian art that had informed his judgment, implying the obvious lack of such sources at the time.Footnote 62

Although Mir iskusstva was not the first periodical to challenge Repin or question Briullov's contribution to the history of Russian art, the iconoclastic art journal took the controversy to a new level. For instance, in his provocative review, Benois reminds the reader of Briullov's status as the great idol (idolishche) of the Russian art world, one whose power was so absolute that even the obdurate Stasov was unable to take him down. But then Benois declares his own opinion of the “idol” in no uncertain terms: “Briullov was not a genius, and not even a very smart man, but simply a brilliant salon conversationalist, rather unbearable at times due to his self-importance and self-delusion.”Footnote 63 Turning to Repin's speech, Benois concedes that, from the point of view of the Academy, Briullov was indeed an excellent draftsman. Nevertheless, despite his “enormous talent,” everything that Briullov had created either stemmed from lies or the desire to astound and please.Footnote 64 Clearly, Benois’ target is not so much Briullov as the entire Academic tradition, which, in his opinion, Briullov and Bruni had “reanimated” dramatically.Footnote 65

Benois’ scorn notwithstanding, one contribution by Briullov seemed beyond doubt: the idea of a “social artist” and art as social practice. As one of the founding members of Peredvizhniki, Vladimir Makovskii opined in his unpublished speech: “With Bryullov's arrival, Russian art became a social phenomenon essential for the cultural development of both Russian society in general and every individual Russian in particular.”Footnote 66 The popular press echoed the sentiments voiced at the jubilee gathering: The Last Day of Pompeii was first of all associated “with the manifestation of general public interest in art and the emergence of Russian art criticism and art literature.”Footnote 67 Briullov's uncontested contribution consisted of “putting up a bridge between artists and society.”Footnote 68 Briullov's other widely-recognized merit was his portraiture. Even Benois allowed Briullov's portraits into his version of Russian artistic canon.Footnote 69 Despite all the categorical pronouncements published in his journal, Sergei Diaghilev, too, did not eschew the “idol” under attack when the future great impresario selected works for his Historical Exhibition of Russian Portraits at St. Petersburg's Tauride Palace in 1905. Over half a dozen portraits by the Great Karl, including those of Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna, Count Mikhail Obolenskii, and Count Pozzo di Borgo, were featured at this landmark exhibition, which was explicitly conceived as a summation of Russian art history.Footnote 70

Although discord prevailed, the 1899 jubilee served to promote Karl Briullov to the status of national hero, even as long-ranging debates about the artist's place in the canon continued. The result of the turn-of-the-century canonization was a particular hierarchy of the greats in Russian culture, as, for instance, Maxim Gor΄kii summarized in 1917: “The giant Pushkin, our greatest pride and the most complete expression of Russian spiritual power, and next to him the magician Glinka and fabulous Briullov.”Footnote 71 In total, Gor΄kii names fifteen writers, artists, and composers who had come to represent the pre-revolutionary canon. Briullov appears at the top of the list in the company of two other founding fathers, Pushkin and Glinka.

As with the Millennium Monument, Briullov here is positioned in near proximity to Pushkin, the “cultural hero” whose company was consequential for the promotion of his fellow greats and whose status has remained largely secure throughout the many political and social changes over the decades.Footnote 72 Due to the strength and stability of Pushkin mythology, the cult of the “first” poet—the Russian designation “pervyi” implying both undisputed greatness and the origin of a new tradition—provided a ready template for adjacent cults. As Marina Frolova-Walker explains with the example of Glinka: “The elevation of Pushkin became the model for later, smaller cults: not only were lesser figures likened to Pushkin in their own sector of the arts, but any chance personal connections to the great poet were also eagerly sought out.”Footnote 73 Both Briullov and Glinka, the mid-nineteenth century's firsts, benefited from their association with Pushkin, as later did Repin, too, when he became the “sun” of Russian painting.

Why should a poet serve as a yardstick of greatness in the field of pictorial art?Footnote 74 The primary reason was institutional. Without a well-established system of art evaluation, Pushkin was “borrowed” from a neighboring art as a benchmark for measuring greatness. With the belated professionalization of the visual arts, there was no ready point of reference within the field to which Briullov could be compared. Pushkin, on the other hand, was the absolute value against which the relative worth of potential founding figures in the adjacent fields (music, painting) could be determined. That Pushkin and Briullov were born in the same year, and were both recognized as Romantic geniuses during their lifetimes, allowed for a peculiar transfer of rhetoric in fashioning Briullov's position as a founding father after Pushkin. Even after the discipline was well established, Pushkin's license to bestow fame was not revoked, as the discussion of Repin's case below demonstrates.

1914 and Beyond: The Afterlife of the Classic

Repin's playful sketch, “Pushkin Begging Briullov for a Drawing,” though perhaps a footnote in the history of canon formation, offers new insight into the story of Karl Briullov as national hero. It was published in the pages of the popular journal Niva (The Cornfield) as part of a special issue prepared by Repin's younger friend, Kornei Chukovskii, to celebrate Repin's seventieth anniversary. Repin had only recently been in the news on account of his Ivan Groznyi i syn ego Ivan (Ivan the Terrible and his Son Ivan), 1883–1885, which had been slashed in January 1913 by a young icon painter in a tragic episode that solicited ardent public support for Repin on the one hand and a vicious attack from young leftist artists on the other.Footnote 75 Niva’s anniversary tribute was an affirmative statement for the aging artist: seventeen pages of the issue included copious reproductions of paintings, reminiscences by Repin and his daughter, poetry, a description of Repin's proposal for a People's Academy of Art, Chukovskii's editorial, and an article by Pushkin scholar Nikolai Lerner that introduced Repin's previously unpublished drawing, “Pushkin Begging Briullov for a Drawing.”Footnote 76

In his article, Lerner recounted an episode from the life of Briullov initially circulated in 1855 by the artist's disciple Mokritskii, whose diary offers many colorful impressions of the art scene at mid-century, according to which Pushkin visited Briullov in the company of Zhukovskii in January 1837, several days before the poet's death. Among Briullov's watercolors, one drawing delighted the visitors in particular: S΄΄ezd na bal k avstriiskomu poslanniku v Smirne (The Gathering for the Ball at the Austrian Envoy's in Smyrna).Footnote 77 Pushkin pleaded with Briullov to give the drawing to him, but it had already been promised to Countess Saltykova. The poet got on his knees, imploring the artist: “Give it to me, dear friend! You are not going to draw another one for me; give me this one.” Still, Briullov refused.Footnote 78

What is remarkable about this story of a minor drawing is its proclivity for repetition. Repin returned to the subject several times between 1912 and 1918, when he was in his early seventies, which indicates its meaningfulness for the aging artist. Three versions of the drawing were apparently produced, the first of which he gifted to Lerner (the original bears the inscription, “To Nikolai Osipovich Lerner”), while the last one was offered to the first director of the Pushkin House, Nestor Kotliarevskii.Footnote 79 Lerner, too, published Repin's 1912 sketch more than once. Prior to the 1914 publication in Niva, another reproduction appeared in the December 1911 issue of Russian Antiquity.Footnote 80 Subsequently, Lerner's essay, “Pushkin at Briullov's Studio,” with an accompanying engraving from Repin's drawing, was included in the six-volume edition of Pushkin's collected works prepared by literary critic and bibliographer Semen Vengerov and published by Brokgauz-Efron as part of the Library of Great Authors series in 1915.Footnote 81

The special issue of Niva, an illustrated weekly with an estimated circulation of 235,000 copies in 1900, reached the broadest audience, and it is in the context of such mass-market publications that artists were transformed in the popular imagination into figures on par with the national genius Pushkin. Not two, but three greats come together in this one image: the Russian national poet, Pushkin, whose reputation as such was sealed during major public commemorations near the century's end; Briullov, named posthumously as the founder of the Russian school of art, whose jubilee celebration in 1899 was tarnished by critics questioning the artist's originality and Russianness; and Briullov's ardent champion, the formerly rebellious Peredvizhnik Repin, whose seventieth anniversary Niva acknowledged with a special issue. The author of the playful sketch “Pushkin Begging Briullov for a Drawing” can thus be seen not only as defending Briullov, who came under fierce attack by the same Mir iskusstva group who ridiculed Repin as well, but also aligning himself with the establishment that both Briullov and now Repin had come to represent. If Briullov was a national hero, so too was Repin. More importantly, in the pages of the illustrated weekly, the artists became popular heroes, familiar and relatable, precisely because the mode of representation was not lofty monumentalism but playful caricature.

While this extemporaneous canonization was proceeding apace, no one seemed to notice that the story which had inspired Repin's drawings may well have been apocryphal. Although it was repeated verbatim in several publications, all of these referred back to one single source: Mokritskii's reminiscences, published in 1855. Curiously, Mokritskii, who kept a diary that was published only during the Soviet era, mentions nothing in its pages about Pushkin kneeling in Briullov's studio.Footnote 82 Nor is the scene mentioned in any other memoirs, although, as Mokritskii suggests, Briullov's studio was always full of visitors. Moreover, according to Mokritskii's diary, Briullov was seriously ill during that time and was not in a position to entertain or pay visits. One may hypothesize, as some scholars have done, that in the spirit of adulation that defined reminiscences about Briullov in the 1850s, some excesses bordering on fiction were inevitable.Footnote 83 Another round of publications centered around Briullov's jubilee in 1899 revived contemporaries’ interest in this memory, which had been originally circulated by the master's students over four decades earlier.Footnote 84 Not only impressionistic memoirs, but the nascent scholarship of the time also seemed to endorse the tale. Thus in his comprehensive volume Trudy i dni Pushkina (Pushkin's Days and Works), 1903, the authoritative edition in the early twentieth century, Lerner included the episode as part of Pushkin's factual chronology.Footnote 85 Briullov's entry in Polovtsov's Russian Biographical Dictionary uses the genuflecting Pushkin as recognizable evidence of Briullov's unsurpassed success in Russia.Footnote 86 Whether the story narrated by Mokritskii was factual or imagined (or something in between) is irrelevant for the present discussion, scholarly curiosity aside.Footnote 87 By the time Repin depicted this amusing scene and Lerner publicized Repin's rendition, Briullov was as much a work of fiction as a historical person.

After several publications in the last imperial decade, Repin's amusing drawing was withdrawn from circulation and remained largely inconsequential for either Pushkin's or Briullov's subsequent reputation. Repin's own fortune, however, was about to change radically—from the first in his field to “our everything” (nashe vse).Footnote 88 The Soviet reshuffling of the art-historical canon allocated to Briullov a perfectly respectful but in no way exceptional place in Russian history. In 1948, he was officially endorsed by Andrei Zhdanov as a beloved and useful classic, along with Repin and a handful of others.Footnote 89 Predictably, Briullov's superior craftsmanship and incipient realism were emphasized above all.Footnote 90 But Briullov was largely uncoupled from Pushkin in the Soviet times; the only connection underscored repeatedly was that the two classics were both “victims of Nicholaevshchina,” as critics referred to Nicholas I's oppressive regime.Footnote 91 Next to Pushkin, Briullov was a founding genius; distanced from the national poet, he became simply a respectable classic, one among several greats.

When the figures of Pushkin and Briullov met again a hundred years later in the jubilee celebrations of 1999, the reception of the two founding fathers again diverged noticeably. While Pushkin's festivities received ample publicity (albeit largely negative, due to the perceived formality of the event), Briullov's celebration, despite significant retrospective exhibitions in the Russian Museum and the Tretiakov Gallery, went virtually unnoticed in the press.Footnote 92 If mentioned at all, Briullov's jubilee was referred to as “forgotten” or “lost.”Footnote 93 Recapitulating Briullov's position in Russian art history on account of his bicentenary, one critic branded him blithely “an average (srednii) European artist” who assumed the status of great simply due to the overall paucity of major talent in the early nineteenth century.Footnote 94

In the twentieth century, Repin became the “sun” of Russian painting, as Boris Sadovskii put it as early as 1914, calling him “The Artist-Sun, our gracious Repin!” (Khudozhnik-Solntse, blagodatnyi Repin!)Footnote 95 This nomination, of course, harks back to “the sun of our poetry,” Vladimir Odoevskii's famous reference to Pushkin in the announcement of the poet's death.Footnote 96 Commenting on Repin's luminary status in Soviet society, Ekaterina Degot΄ points out that all major canvases of Russian art, whether Viktor Vasnetsov's Bogatyri (Epic Heroes) or Valentin Serov's Devochka s persikami (The Girl with Peaches), are routinely attributed by the general consumer to Repin.Footnote 97

“The Pushkin” of Russian visual arts in the Soviet era is not Briullov, but Repin. Aside from over seventy exhibitions of the artist's works, four museums have been established and several monuments to Repin have been installed in various cities, including one on Bolotnaia Square in Moscow in 1958.Footnote 98 This way Repin was inscribed into the tradition of 19th-century jubilees, as exemplified by Pushkin's and Gogol΄’s commemorations, which placed monuments in the center of festivities.Footnote 99 By contrast, aside from his representation on the Millennium Monument, no major statues of Karl Briullov were created, either during his big jubilee or beyond. A copy of a bust by sculptor Ivan Vitali, crafted during Briullov's stay in Moscow in 1836, was installed in Mikhailovskii Garden in St. Petersburg only in 2003; another bust to Briullov was unveiled just recently in 2013 in the Municipal Gardens of Funchal, Madeira (Portugal).Footnote 100

The pragmatic utilization of classics in Soviet society is well known; some authors even argue that the spirit of socialist realism was born out of the cult of imperial classics.Footnote 101 The conspicuous rise of Repin dates to 1936, when a major “all-union” exhibition of nearly one thousand works was launched successfully in Moscow, Leningrad, and Kiev. Shortly thereafter, in a monumental edition devoted to the artist, published in 1937—a year that saw another round of major anniversary celebrations for Pushkin—Igor΄ Grabar΄ represented Repin as “the hero of his time” and the only artist worthy of emulation in the era of socialist realism.Footnote 102 A decade later, Grabar΄ paired Pushkin and Repin explicitly, describing the “favorite artist of the Soviet viewer,” one appreciated by the entire nation, in terms of Pushkin's poetry.Footnote 103

Thus was Repin canonized by Stalinist culture as “the sun of Russian painting” and the “main” (glavnyi) artist; like Pushkin, he became the generalissimo of his field.Footnote 104 If in his own day Repin's superior position in the world of visual arts had been habitually likened to that of Tolstoi in literature, as well as Tchaikovskii in music, in Soviet and early post-Soviet times, he was more readily compared to Pushkin.Footnote 105 To a certain extent this cultural mythology survives today as well. The widely read newspaper Argumenty i fakty (Arguments and Facts) offered the following analogy in a recent publication commemorating Repin's 170th anniversary in 2014: “Il΄ia Repin is like Pushkin. Literally, our everything.” And further: “Repin's canvases for our fellow countrymen are basically like Pushkin's poems. You do not remember them, but they are always with you.”Footnote 106 The cult of Karl Briullov as the “first” and the “greatest” artist was replaced by the cult of Repin.

Pedestrian as this discourse may sound, it is useful to compare precisely this sort of popular writing, as opposed to scholarly publications, as a gauge of an artist's reputation in society at large. Snippets of opinion from mass-circulation periodicals offer a window into the kind of writing that made Briullov's and later Repin's fortune. The popularity of these artists, both of whom contributed greatly to the dissemination of visual arts in Russia, should not be ignored. Aleksei Bobrikov, for one, argues that it was specifically due to the mass appeal of his canvases that in the later 1880s Repin increasingly came to occupy the position of the “first” Russian artist once held by Briullov.Footnote 107

Today, the cult of Repin is gradually being dismantled in scholarly publications as well as in recent exhibitions, and in post-Soviet Russia, he shares the nomination of “first” with such previously underrated artists as Kazimir Malevich and, most recently, Valentin Serov, whose exhibition in 2015–16 proved phenomenally popular.Footnote 108 “Serov now is our everything … The Pushkin of Russian painting,” wrote one reviewer of that remarkable exhibition.Footnote 109 Briullov and Repin have both turned out to be replaceable as “the Pushkins” of Russian painting.

In post-Soviet Russia, Briullov continues to occupy a canonical position of a reliable classic. His heritage is no longer a source of controversy, and occasional publications and exhibitions devoted to the one-time “colossus” receive for the most part well-tempered reviews. Intermittent new discoveries of his works, of which there were several in the past decade, continue to cause moderate stir. Such was the case with two exhibitions in the Russian Museum in 2013, one introducing ten previously unseen canvases from Russian private collections, the other, titled appropriately “The Famous and Unknown Karl Briullov,” put on display the artist's drawings and sketches, notably from the so-called “Italian Album,” which for 150 years had remained in the Wittgenstein family and was only recently repatriated.Footnote 110 Occasionally the artist attracts his share of scandal, too, as most recently was the case with the “arrested” painting by Briullov, the previously unknown Khristos vo grobe (Christ in Coffin), which was confiscated from its rightful German owners as a cultural valuable of the Russian Federation and placed for safekeeping in the Russian Museum.Footnote 111

Much as in previous centuries, the conversation around Briullov, more than his artworks per se, reanimates the retired national hero and (temporarily) restores his art into circulation. The public figure of the artist consists of both an affirmative, laudatory discourse and a dissenting counter-discourse. Briullov the artist remained larger than life as long as he existed in the Russian public sphere not as a permanent fixture, but as a controversy. With his reputation suspended in public opinion between a “world-famous genius” and a “bloated mediocrity,” Briullov evolved into the protagonist of many written texts and pictorial narratives. Part fact, part fiction, this voluminous output was subject to changes in taste and critical evaluations. The dynamics surrounding other contemporary “giants” of the Russian art world, including Repin, repeated Briullov's sharp vicissitudes of fortune. The instability of this scenario, however, does not undermine the status of the artist, but on the contrary, invites the public to participate in these ongoing debates, now accepting, now contesting nominations for national heroes.